| Communication |

|

Communication media catering to mass audiences has hitherto ignored the vast discrepancy in visual language between the urban audience and the rural audience. Visual perception is defined as the way a person "reads," interprets or understands a picture. Since differences in cultural environment and personal experience significantly affect perceptions, the visual language of a group is acquired over time with respect to their surroundings. |

Visual literacy: the urban-rural discrepancy

|

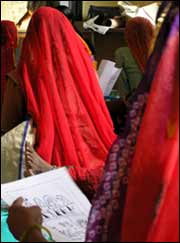

In urban mainstream art institutions, communicators are taught to draw what one sees; however, rural people draw what one knows. For example, a tree would be drawn with roots included, even if the artist may not actually see the roots as illustrated in this picture. |

|

The urban artist is also instructed to pay attention to detail and produce photo-realistic images that include detailed background, depth, and vanishing-point perspective. These elements of formally educated artists are unrecognizable to rural audiences and complicate the intended messages: " This represents a cot or "khat" All legs of the cot are shown". |

|

Rural audiences also have difficulty recognizing objects that are superimposed, parts of object hidden behind one another. Instead, rural artists draw images in multiple perspectives: the object is drawn as if it were twisted, to include all possible side views. |

|

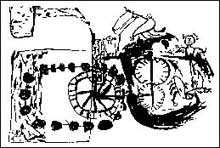

The use of multiple perspectives, the combination of aerial and side views, has origins in traditional art in Rajasthan. This is a picture of the rehant or bullock drawn water wheel. The pots cannot actually be seen as they are hidden below the surface of the water; but by drawing the image through top or aerial view renders the water lifting process visible. Simultaneously, the farmer and his bulls are drawn in side view. While there are only two bulls drawing water, they are drawn twice. This is to indicate the motion or movement of the same pair of bulls. In this manner, time can be shown continuously with the same object or figure in different actions in a single-frame visual. |

|

Reading a visual, like text, from left-to-right and top-to-bottom is acquired through formal education; on the other hand, rural audiences tend to scan the entire visual. Since visual narratives are a part of rural pictorial traditions, rural artists draw single - frame narratives that weave events into a story. |

|

A group of women was asked to design their own posters. Sonibai and Badibai of Sagwara village were involved in a significant struggle to save their sagwan or teak trees. Through illustration, they composed a visual narrative of the events of the struggle. The story goes: timber contractors were cutting down trees from their hills. Everyone in the village was worried. They beat drums and collected all the villagers to decide how to proceed. A meeting was held. They blackened the faces of the contractors and drove them out of the village, and ultimately sent to jail. The visual is a narrative and thus has a sequence; however, the events are shown without sequence. |

| This reveals the misconception that visuals are read left-to-right and top-to-bottom. Unnecessary background is absent, bringing the focus on the villagers and their actions. Furthermore, the rural women visualize the message of "stop" or "don't do" by a hand gesture of reaching out two open hands. This replaces the urban symbols of the cross, and was integrated in subsequent communication visuals. The representation of a meeting in the bottom left corner is drawn in mixed perspective. The women in a circle are drawn in aerial view, while the man in the center is drawn in side-view. The gender differentiation between the male leader in the center of the meeting and the surrounding women also reveals power relations between men and women. The control of the village's thought process is typically concentrated in the hands of a few people, always men. The women incorporated this imbalance into their drawing, accepting it as expected. Yet, in inquiring about this issue, the women can also question the existing practice and even challenge these ideas. Therefore, the drawing sessions can provoke discussion and introspection. | |

In a picture recognition exercise in a village 100 km away from the Sagwara village, other women also understood this picture, indicating that visual language is often similar among other non-educated women. Yet, the assumption cannot be made. Field testing in every village and to local audiences is still indispensable to comprehension and effective implementation.